Prehistory and proto-history in the Upper Agri Valleyby Salvatore Bianco, Ada Preite, Elena Natali

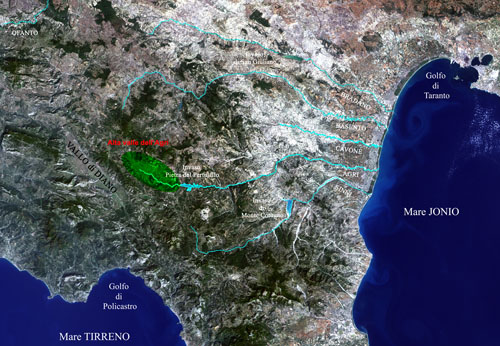

The Agri Valley goes through Lucan Apennines following the direction northwest-southeast for about 50 kilometers. In the initial part it is wide and open, in correspondence of the lake basin of Pleistocene era, while in the middle part is narrow and winding, in correspondence of the current artificial lake of Pertusillo; it expands, gradually, through the formations of “hills of Matera”, in the part of middle-lower river course to flow into Ionian coastal plain of Holocene era. Agri river is an ancient natural way of linking Tyrrhenian and Ionian sides, used since the prehistory as way of trades as well as cultural and commercial exchanges.

The Upper Valley, occupied by man since ancient time and now intensively cultivated because of the presence of water and the fertility of soil, noticed the settlement of many rural villages since the middle of last century, organized according to the model “spread and linear”, that overlapped on small hamlets and farms of eighteenth and nineteenth century. Archaeological researches, carried out during the realization of the oil pipeline Mount Alpes-Taranto, allowed to redefine the chronological and cultural frame of the prehistoric and proto-historic human settlement in the Upper Agri Valley, highlighting the strategic and economic role already played in so ancient times. This allowed the inclusion of this area in all ideological, cultural and material manifestations that characterize with different aspects and results the prehistoric and proto-historic stages in Basilicata.

The Upper Agri Valley is occupied by humans already since Paleolithic, but a more intense human settlement begins just from Neolithic onwards. Remains of fossil fauna of big pachyderms (Straight-tusked elephant), are known from the territory of Grumento Nova; similar to species of other lake basins of the region (Venosa, Matera, Atella, Mercure), these remains are dated to Middle Pleistocene, period in which the climatic oscillations still permitted the life of its faunal sets, then extinct.

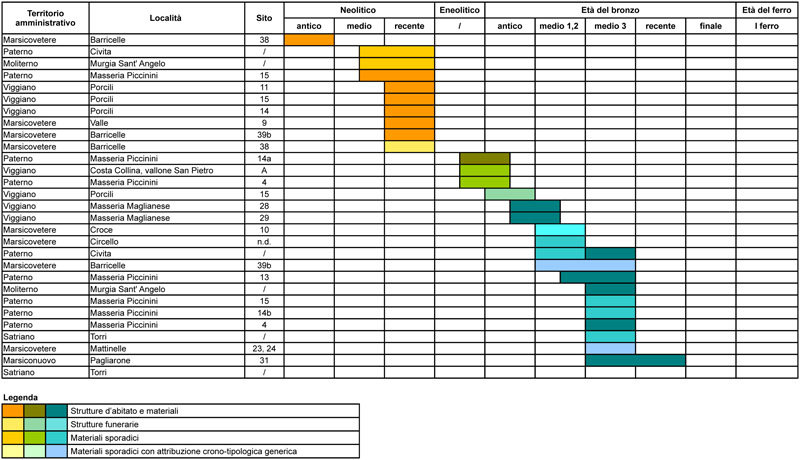

From the ancient era to the final one of Neolithic (about sixth-fifth millennium B.C.), the man settles in the upper part of the valley, taking advantages of hills and valleys areas of Marsiconuovo, Marsicovetere, Paterno and Viggiano.

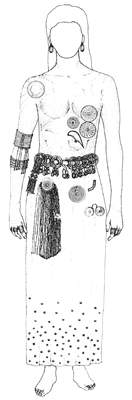

Rarer were the funerary spaces, at the moment documented in the upper valley just from some burial places accompanied by ceramic and lytic kit. The trade with other cultural and geographical places is documented by the presence of non-autochthonous material, such as obsidian, coming from Aeolian Islands and/or from Calabria. Neolithic religion, better known in other areas of Basilicata (Melfi, Matera, Middle Agri Valley, Ionian area) is based on the cult of land/man’s fertility and agricultural cycles with offers of vegetables and/or animal sacrifices. The Mother Goddess, symbol of fertility, is represented with idols depicting the woman with breasts and pelvis protrusive. Moreover, refer to fertility beliefs the profiles of human face, reproduced on the edges of pots from early and middle Neolithic, and heads of animals (anatidae, rams, bulls, dogs) applied on the handles pots from middle-late Neolithic from culture of Serra d’Alto.

In the Upper Agri Valley, at the moment, there aren’t any burial structures dating to late Eneolithic. The sample topographically nearest is in the Middle Agri Valley, where is documented the presence of burial barrows, expression of the acquisition of new burial and symbolical beliefs, as well as demarcation indicators for the community area.

Meetings, exchanges and socializations, favored by commercial activities (products trade, transhumance, etc.) stay at the base of cultural uniformity that is emerging in the Upper Agri Valley during the late phase of Middle Bronze Era, thanks to the emerging of Apennine culture. During this period, human groups socially and economically well-structured, occupy both hill and valley areas strategically important.

The topographical features of hill settlements, located on natural acropolis, easily tenable, put them in a dominant position on the surrounding area and at the middle of a thick system of fluvial valleys and passes that link the different territories in rapid and reciprocal communication. These environmental aspects certainly contributed to the development of material and cultural contacts among the communities; contacts that during an advanced stage of Middle Bronze Age made possible the establishment of an “unique cultural area” among the settlements of Upper Sinni Valley and Upper Agri Valley. Cultural area that in turn falls within in the larger “cultural area of Tyrrhenian gravity”, formed by western Basilicata, coastal areas and islands of Campania, Tyrrhenian Calabria and Aeolian Islands. The first cultural manifestations of the early Iron Age (first millennium B.C.) in Basilicata, are the result of evolutionary processes already begun in the previous stages and influenced by cultural models of Illyrian-Balkan derivation. The settlement choices continue to prefer the hills with possibility of control of territories and surrounding routes, which promote cultural relations and economic activities. In the Upper Agri Valley, the early Iron Age is poorly documented, whereas in the middle and low part of the fluvial valley in this period are developing settlement realities of Oenotrian culture, mainly known through the rich necropolis, often with continuity of life between tenth/ninth century and fifth century B.C.

Bibliography:

Copyright text and pictures (where there aren’t other references) by Salvatore Bianco, Ada Preite ed Elena Natali. |

The Upper Agri Valley, geomorphologically correspondent to the Pleistocene lake basin, is a wide hollow of elongated oval shape. It is bordered by mountains (calcareous-silicon-marly), nowadays bare, but in the past covered by woods and places of settlements perched, located in a strategic position to control the valley and transport links with adjacent hydrographic basins.

The Upper Agri Valley, geomorphologically correspondent to the Pleistocene lake basin, is a wide hollow of elongated oval shape. It is bordered by mountains (calcareous-silicon-marly), nowadays bare, but in the past covered by woods and places of settlements perched, located in a strategic position to control the valley and transport links with adjacent hydrographic basins.

The presence of man in the upper valley is testified only during Middle Paleolithic, of which are referred lytic industries on flake and blade of

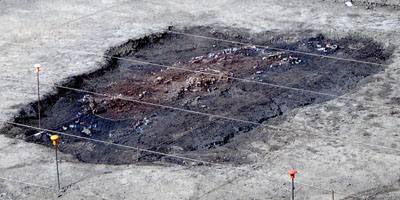

The presence of man in the upper valley is testified only during Middle Paleolithic, of which are referred lytic industries on flake and blade of  In these areas are documented living settlements with remains of huts (holes for post, pits for combustion, trellis/plaster, fireplaces, etc.), remains of clay pots made to hold and preserve solid food such as wheat and barley, and liquids, such as milk and water, millstones and stone pestles used for grinding grains, lytic instruments (flint and obsidian), bones and faunal remains such as meal and butchery remains both of domesticated species, which refer to farm animals (sheep and cattle), maybe subject to brief transhumances, and wild species, subject to hunting.

In these areas are documented living settlements with remains of huts (holes for post, pits for combustion, trellis/plaster, fireplaces, etc.), remains of clay pots made to hold and preserve solid food such as wheat and barley, and liquids, such as milk and water, millstones and stone pestles used for grinding grains, lytic instruments (flint and obsidian), bones and faunal remains such as meal and butchery remains both of domesticated species, which refer to farm animals (sheep and cattle), maybe subject to brief transhumances, and wild species, subject to hunting. The beginning of Metal Age (about late fourth millennium B.C.) is marked both by the arrival of

The beginning of Metal Age (about late fourth millennium B.C.) is marked both by the arrival of  In the Upper Agri Valley the

In the Upper Agri Valley the  The same funerary model is kept almost unchanged in the subsequent

The same funerary model is kept almost unchanged in the subsequent  These are communities whose remains indicate a particular uniformity settlement and material in the use of vascular forms, often decorated, in particular those related to the storage and processing of milk (jars, small jars, boilers, bowls and pigeon cups with handles surmounted by raising, sometimes with a central hole), suggesting the adoption of a complex economy characterized by the practice of agriculture, farming, hunting and craft.

These are communities whose remains indicate a particular uniformity settlement and material in the use of vascular forms, often decorated, in particular those related to the storage and processing of milk (jars, small jars, boilers, bowls and pigeon cups with handles surmounted by raising, sometimes with a central hole), suggesting the adoption of a complex economy characterized by the practice of agriculture, farming, hunting and craft. The topographical evidence and the archaeological importance suggest that the settlements on hills and valleys were object of seasonal frequentations, probably linked to the practice of summer transhumance in short and medium range (valley ↔ hill ↔ mountain). We don’t have to preclude, however, that hill areas, due to their topographical position, have played an important rule also on a longer path, that from Agri Valley, going westwards, through many easy passes, leading to the

The topographical evidence and the archaeological importance suggest that the settlements on hills and valleys were object of seasonal frequentations, probably linked to the practice of summer transhumance in short and medium range (valley ↔ hill ↔ mountain). We don’t have to preclude, however, that hill areas, due to their topographical position, have played an important rule also on a longer path, that from Agri Valley, going westwards, through many easy passes, leading to the